| Major-General Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse, GC

DSO, died at Waterloo, Belgium, on March 26 1989, at the age

of 77. He was born in Brussels on April 5, 1911, and read

medicine at Brussels University before joining the Belgian

Army.

Under the cover name of Pat O'Leary, a name borrowed from a peace-time Canadian friend, he ran one of the biggest and best of the escape and evasion lines of World War II. |

|

From Dr. Guérisse to O'Leary RN

Guérisse was Médecin-Capitaine with a Belgian cavalry regiment during their eighteen day campaign in May 1940. He managed to escape to England through Dunkirk. Unimpressed with the early efforts at setting up a Belgian Government in exile he took up with the crew of a former French ship, the Rhin. This heavily armed merchantman of Marsellais origin had been renamed HMS Fidelity and was serving in the Mediterranean on secret missions.

He secured entry into the British Navy and was commissioned as Lieutenant Commander Patrick Albert O'Leary RN, taking the name of a Canadian friend. He told no-one but the Captain of the Fidelity of his medical background, preferring adventure rather than the duties of an MO.

His entry to the Royal Navy instead of the RNVR followed the precedent set by his friend Peri, Captain of the Fidelity, who adopted the nomme de guerre Langlais. Peri had noticed that the gold lace on his uniform cuffs was wavy, unlike that of other RN Captains.

When told that it was wavy because he was RNVR, being a wartime holder of a temporary commission, he advised their Lordships that neither he nor his ship would fight unless Captain Langlais RN was on the bridge of the Fidelity. The Admiralty compromised by allowing him to wear RN insignia. Peri had also came with a lady friend whom he insisted be part of the crew. Again the Admiralty gave way and she was signed on.

Early on 25th April 1941 two SOE agents were put ashore by skiff from the Fidelity on a beach at Collioure near the Etang de Canet. Returning that night the skiff overturned in a squall:from it Guérisse managed to swim ashore.

Not long afterwards the Fidelity was lost with all hands when torpedoed in the South Atlantic.

Recruited by Ian Garrow

Guérisse passed himself off as Pat O'Leary, an evading Canadian airman, to the French coastguards who came to arrest him. He was sent to St Hippolyte du Fort near Nîmes. Here he was among British officers held under conditions of not quite being prisoners, not quite being free. His fellow inmates regarded him with some suspicion until he was able to prove his identity as an RN officer.

He was sprung from Fort St Hippolyte by Ian Garrow, a Captain in the Seaforth Highlanders working in Marseille to assist evaders and escapers. Garrow worked closely with Donald Darling : in 1940 Darling had been provided to MI 9 by MI 6 to help run an escape line from Marseille into Spain, working under the cover of British vice-consul in charge of refugees based in Lisbon. His code name was 'Sunday'.

|

From now on in this account,

Guérisse will be referred to as O'Leary.

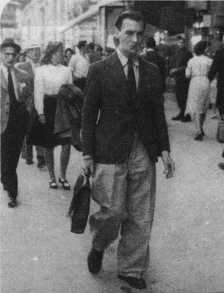

As the Marseille organisation was not fully convinced O'Leary was who he said he was, Garrow arranged for a coded message to be broadcast by the BBC if checks in London confirmed he was genuine. A fortnight later on the 9pm news O'Leary heard "Adolphe doit rester" - London's message saying he was all right. Garrow and O'Leary set up from a Marseille base a system that became highly efficient at moving escaped Allied POWs and shot-down airmen who had evaded capture, out of France into Spain and so to Britain. Left: O'Leary looking unhappy at being snapped by a

Marseille street photographer in 1941. |

Pivotal to the Marseilles end of the network was a local doctor, Georges Rodocanachis. Liverpool born, he had become a naturalised French subject.

Garrow had been involved almost from the start in the efforts of Marseille people - like the doctor and his sister in law Madame Zarifi, and Reverend Donald Caskie of the Seaman's Mission, in looking after the British servicemen and civilians accumulating in the city after the fall of France.

Now his concern was how to get valuable trained people back to Britain. Ian Garrow's story is related by Christopher Long in Secret Papers, MI9, SOE & 'Pat Line'

O'Leary takes over

In October 1941, when the French at last caught up with Garrow, O'Leary took over command of the line, thenceforth officially known as the P.A.O. line (his initials) but more famously as the "Pat" or "O'Leary" line. It was built around a mixed group of men and women - French, Scots, Jews, Australasians, Greeks and even Germans opposed to Hitler. O'Leary's firm and unobtrusive leadership inspired them all.

The line expanded to cover occupied as well as unoccupied France. It carried over 600 people to safety, including Airey Neave on his way back from Colditz: Neave was to become one of the key players ('Saturday') in the command of MI 9. O'Leary travelled frequently between the Dutch frontier and the south of France, himself escorting the 'parcels' through numerous German controls to inspire the confidence of his colleagues.

Foot and Langley in their excellent book MI 9 Escape and Evasion 1939-1945 said of the O'Leary Line: 'Its great strength came from the fact that the people who formed its guiding core all knew, liked and trusted each other. They understood each other quickly, without long explanations; they were all well aware of the risks they ran, individually and in common.

The enormous advantages of this inner cohesion were offset by a countervailing, catastrophic snag: one of the helpers was no good. His companions, being the sort of people that they were, did not take this in till he had handed 50 helpers over to the Gestapo.' [see Cole]

O'Leary rescues his rescuer

When Garrow was arrested by the French Vichy police in October 1941 he was sentenced to 10 years detention in a concentration camp at Mauzac. O'Leary now set about repaying Garrow for getting him out of St Hippolyte du Fort. He had a guard's uniform made and by means of bribery it was smuggled in to Garrow. At dawn on 6th December 1941 Garrow got out among the night shift of guards coming off duty. London insisted he return to England.

Before they parted O'Leary asked Garrow how much longer they could continue. This same concern was later to be be considered in London by Airey Neave who himself passed down the line in April 1942.

Le Neveu strikes

The end was not that far off. Tom Groome, their radio operator, was arrested in a routine direction-finding check. He had failed to post a look-out. In Toulouse he leapt out of a window during interrogation, fell 30 feet and hobbled off, only to be given up to the pursuing Gestapo. Fortunately his courier was able to get away and report to O'Leary as much as she knew.

Groome, with a gun in his back, managed to omit his security check when he was forced to transmit to London. Alerted by this, when Groome next transmitted, Colonel Dansey of MI6 himself directed the reply, taking the opportunity to 'frame' the chief of police in Genoa, against whom Dansey had a genuine grudge dating from before the war.

And then there was the fear of what would happen when the Gestapo eventually got round to interrogating Harold Cole, held in a Vichy prison.

In January 1943, Louis Nouveau one of the organisers in Marseille had been approached in Paris by a Roger Le Neveu, who offered his services as a guide. Unable to contact London after Groome's arrest, Nouveau was on his own. He decided to test Le Neveu with small jobs. Satisfied, he gave Le Neveu a party of seven airmen to take south. They arrived safely, as did a second party. Nouveau accompanied Le Neveu with a third party of five airmen. All seven were arrested when changing trains in a suburb of Tours.

Le Neveu met O'Leary in a cafe in Toulouse in early March. O'Leary asked him if he knew who had been betraying the Line in Paris. 'Yes' said Le Neveu: O'Leary was arrested on the spot.

Facing the end in Dachau

Within three weeks London knew O'Leary had been captured. O'Leary took all the responsibility on himself, to prevent further damage. A young member of the Line, Fabien de Cortes, was helped by O'Leary to jump from the train on their way to Paris. Cortes managed to reach Geneva where he relayed what O'Leary had told him about Roger Le Neveu (alias Roger Le Légionnaire, possibly an associate of Cole). De Cortes returned to France and was soon arrested; he, Groome and Louis Nouveau all survived their concentration camps.

O'Leary was tortured to make him reveal the names, duties and whereabouts of the other members of the line. He was put in a refrigerator for several hours and then beaten continuously but did not disclose any information of use to the Germans. He was then held under the Nazis' infamous Nacht und Nebel procedure in a series of concentration camps, beginning at Natzweiler and ending at Dachau.

He was again tortured at Dachau and sentenced to death. Fortunately the war ended before the sentence was carried out. Even the SS had failed to break his irrepressible spirit, and when the Allies in April 1945 reached Dachau they found the camp had been taken over by "O'Leary".

As the prisoners' 'president' O'Leary refused to leave Dachau until he had ensured that all possible steps had been taken to relieve his fellow inmates' condition.

After the war

Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse was born in Brussels on April 5, 1911, and read medicine at Brussels University before joining the Belgian Army. The alias of 'Patrick O'Leary' came from a peace-time Canadian friend.

After the war he returned to serve in the Belgian Army. He was wounded in the Korean War while rescuing a casualty and was decorated once more. He was to become head of the Belgian Army's medical service, before retiring in 1970 with rank of major-general.

| Guérisse remained always a gentle,

humorous, unassuming man, unless a tyrant or a villain roused

him; then his anger could be terrible.

He was awarded the George Cross in 1946 for his outstanding wartime gallantry, and had received the DSO in 1942. He was once described as the most decorated man for bravery alive and held 35 decorations from various countries. In 1964 he was the subject of a This is Your Life television programme. He was made an honorary KBE in 1980 and, not long before he died, King Baudouin of Belgium ennobled him as a count. In 1947 he married Sylvia Cooper-Smith, who pre-deceased him. Their son survives him. |

Sylvia Cooper-Smith and Guerisse after he received his George Cross in 1946 [courtesy Christopher Long] |

(2 April 1989 - Helen Long added in a letter to The Times) Further to the obituary [in The Times] on Maj-Gen Albert Guérisse (March 29), who ran his escape line from the flat of my uncle, Dr Georges Rodocanachi in Marseille, I well remember interviewing him at his home in Belgium in connection with research for my book Safe Houses Are Dangerous.

Having been provoked into landing a punishing blow to the traitor Paul (alias Harold) Cole in the Rodocanachis' flat in 1941, Guérisse was left with a fractured and misshapen right hand. Why, I asked him when he displayed the deformed knuckles at my request, had he not got Doctor Rodocanachi to set it for him then and there?

His reply was that his cover as Lieutenant-Commander Patrick O'Leary was all important. "As a fellow doctor I would surely have betrayed and been unable to hide from him my medical knowledge and both of us would have been compromised since my cover would have been blown," he explained. As it was it served him through years of unparalleled gallantry till the Allies' victory.

When his English wife, Sylvia, was taken terminally ill I accepted that his promised foreword for my book would no longer be forthcoming. And yet I felt that he would never fail me. Nor did he. A man who could spring his friends from captivity despite all the odds was not going to let me down as my book was going to press. Like many, I shall never forget his legendary charm and audacity.

Sources:

Obituary: The Times, 29th March 1989

MI 9 - Escape and Evasion 1939-1945: MRD Foot & JM Langley

Safe Houses are Dangerous: Helen Long

Saturday at MI 9: Airey Neave

Home Run: Richard Townshend Bickers

see also

Royal

Air Forces Escaping Society 1945-95

Royal

Air Forces Ex-POW Association

Further information, updates, and links on

this subject are welcome.

Last updated 27 Nov 2001

Harold Cole - 'Paul'

'Captain Harold Cole' was one of the O'Leary Line's most active helpers in northern France. However, it was found that no such officer called Captain Harold Cole existed in the Army at the Dunkirk period.

Scotland Yard records did throw up a petty criminal, called Harold Cole, who had trained as an engineer. He was known as a con-man and housebreaker. A Sergeant Harold Cole had absconded from the BEF in the Spring of 1940 with the sergeants' mess funds in his charge. When France was occupied he turned up in Lille as 'Captain Harold Cole' of the British Secret Service.

His French had a strong English accent and when questioned by the Germans he would claim to be deaf and dumb, pretending to use sign language. He did organise a genuine escape line from Lille and those involved have told of his audacity when escorting evaders at that time.

In September 1941 O'Leary sent a young attractive French girl to work as a guide with Cole and over the next three months she and Cole took 35 evaders from Paris over the Demarcation Line between Occupied and Vichy France. Late in December 1941 they were married.

By the Autumn of 1941 Donald Darling ('Sunday') working from the British Embassy in Lisbon, became suspicious about Cole. In January 1942 Darling moved to Gibraltar, nominally as a civil liaison officer but actually to interrogate every arrival claiming to be an escaper or evader - military or civil - passing through from occupied territories. He was in a good position to pick up concerns about security.

Cole had been provided with large funds for Duprez, a Lille helper. When O'Leary checked on this, Duprez claimed nothing had reached him: Duprez and O'Leary crossed the Demarcation Line intending to report their suspicions about Cole to Garrow. On reaching Marseille they heard that Garrow had been arrested. In December of 1941 O'Leary ordered Cole to Marseille to confront him with a charge of misappropriating the Line's funds.

A meeting with Cole was arranged in Dr Rodocanachi's flat in the Rue Roux de Brignoles. Cole denied O'Leary's accusations of misappropriation. When O'Leary brought Duprez into the room Cole appeared shocked. He moved towards O'Leary who knocked him down with a blow to the mouth, O'Leary severely injuring his fist in the process. As Cole lay injured on the floor, he made a sort of confession.

Cole was locked in the bathroom whilst O'Leary and those with him (including Prassinos and Bruce Dowding) discussed what they should do with him - kill him or send him back to England? A noise from the bathroom alerted them - Dowding caught sight of Cole escaping through the bathroom window. A chase ensued but Cole managed to get away and returned to Lille.

Warnings went out to the Line but it was difficult for many to believe that an Englishman could have turned traitor. Duprez, for example, refused to move and change his name, preferring to stay with his family and business.

Later it emerged that Cole had been arrested in Lille by the Abwehr on December 6th 1941 and it was presumably at this point that he changed sides. Cole was probably threatened with execution and was described as having a 'yellow streak' in his character, according to Neave.

The Abbé Carpentier had been using his own printing press to provide the line with identity cards and passes. On December 8th 1941 Cole helped two Germans disguised as RAF evaders to arrest the Abbé. Dowding, who was hiding in the house, recognised Cole's voice and on escaping he rushed to warn other agents in the area. However Cole had given the Germans many addresses and at the third of Dowding's warning visits they were waiting for him and arrested him.

It was a letter from the Abbé smuggled out of Loos prison, which reached O'Leary several months later that detailed the extent - 30 written pages of names and addresses - of Cole's betrayal of the O'Leary Line. Duprez, Dowding and the Abbé were all badly treated and later executed.

In March 1942 O'Leary came out on his own escape line to attend a meeting in Gibraltar with Darling and his boss Langley. O'Leary found his own doubts about Cole confirmed and it was decided that Cole should be executed on sight. All the intelligence services were warned about Cole and steps were taken to protect those who Cole may have been able to compromise.

Apparently the Abwehr office in Brussels then used Cole - operating with several aliases including Delobel, Joseph Deram, Richard Godfrey - extensively to penetrate the Line. Neave says that whilst there was no firm evidence about Cole's agreement to work with the Germans, it seems probable he was 'persuaded' to do so by Sonderführer Richard Christmann of the Abwehr. The latter had already penetrated several SOE circuits in France using a bogus escape line. Christmann also worked with Colonel Giskes on the Nordpol deception of SOE in Holland.

In April 1942 Cole and his wife crossed the Demarcation Line and were soon arrested in Lyon on the orders of the pro-Allied head of the Lyon DST, Louis Triffe. Aware of the stories of Cole's collaboration, Triffe sought to protect resistance organisations in the Unoccupied Zone.

Cole's wife, now pregnant, would not believe that her husband was a traitor until a French detective hit him in the face, whereupon Cole confessed. The Coles were tried by court-martial on charges of espionage and delivering French citizens into the hands of the Germans. Cole was convicted and sentenced to death.

His wife was acquitted: she returned to Marseille in August 1942 and contacted O'Leary, after having writing a bitter letter to Cole. On 30th October 1942 she had a son, who died in January 1943. She again took up resistance activities but was arrested by the Germans when they occupied Vichy France. She held out against their interrogations on the O'Leary organisation and eventually escaped to Paris in September 1943.

Cole, who had denounced her, was released to search for his wife in the winter of 1943. Fortunately, she was lifted from Brittany by the Royal Navy in April 1944. She underwent SOE training, survived the war, remarried, and lived until the end of the century.

What of Cole? In 1944, when the Gestapo was now in overall charge of police operations in France, Cole was working for SS Sturmbannführer Richard Kieffer, head of the SD in Paris. Following the Allied invasion, Cole was again denouncing people involved in hiding airmen in the round up, executions and deportations of hundreds of resistance workers carried out by a vengeful Gestapo and SD in June 1944. Neave was told that Cole had left Paris dressed as a German officer on 17th August 1944.

In the Spring of 1945 Cole surfaced again in the American Zone of Occupied Germany, masquerading as an English Captain called Mason: he claimed to be working on an intelligence task. With him was SS Sturmbannführer Richard Kieffer of the SD, for whom he sought a safe conduct in view of the latter's usefulness.

Cole was rewarded by the Americans with the rank of Captain and an interrogation job in their Counter Intelligence Corps. He promptly used this to denounce his former Gestapo and SD colleagues.

In August 1945 Darling was by now head of the MI 9 Awards Bureau in Paris, seeking to identify genuine helpers. He was approached by one of Cole's mistresses. She claimed that Cole was in fact not a traitor as he was working as an Intelligence Officer for the Allies. She showed Darling a note from Cole, from which he quietly noted the address. He contacted French and British Security and Cole was arrested at a cocktail party at the HQ where he was working in the American Zone.

He was brought to Paris and identified by Rev Donald Caskie, the Scarlet Pimpernel of the Marseille end of the O'Leary Line. Held in American custody, Cole managed to persuade his guards that he should be allowed to write his 'memoirs' in the prison guard room. Unfortunately he was not closely enough watched and slipped away in American Sergeant's jacket.

According to Neave, Cole convinced the proprietress of Billy's Bar in the Rue de Grenelle that he was a US Sergeant waiting for his demobilisation and he stayed in hiding above that establishment.

Although the French BCRA were looking for him, it seems that it was a routine police search for deserters that brought Cole's end. Two gendarmes had been warned that someone was in hiding above Billy's Bar. When they knocked Cole appeared, holding a pistol. He fired three times, wounding one of them, but they returned fire, shooting Cole dead. His body was identified by Guérisse, recently released from Dachau.

Cole was a traitor to his country. He betrayed about 150 French people who worked for the Allied cause, of whom it believed 50 - mostly involved with the O'Leary Line - gave their lives. He is even said to have helped the Gestapo to torture some of those he betrayed. He also deceived his wife, sending her on false errands to collect airmen and later denounced her aged aunts who had hidden airmen, in order to steal their jewellery.

In retrospect Neave believed that had there been effective radio comunication with London at the time, the damage Cole caused, or much of it, might have been avoided. Communication with London was still reliant on messages concealed in toothpaste carried by couriers over the Pyrenees.

Roger Le Neveu/Roger le Légionnaire

In his book Saturday at MI 9, Airey Neave says that Le Neveu was one of several Frenchmen who were bribed or blackmailed to work against their countrymen.

Following O'Leary's arrest Le Neveu was moved to the Rennes Gestapo to break up the Shelburne Line in Brittany.

In July 1943 the Gestapo searched the

Château de Bourblanc, near Paimpol in Brittany, the home of Comte and

Comtesse Betty de Maudit, an American. She was arrested and sent to

Ravensbrück concentration camp. Earlier in the year a visitor from

London had found 'a whole regiment' of American and British airmen in

hiding there. Le Neveu is strongly suspected of having betrayed her.

Some arrests among those he invited to send airmen to him in Paris

generated suspicion of him and so the principal Brittany organisation

stayed intact. He appears to have done relatively little damage in the

area after 1943, though he was still attempting to penetrate routes to

Spain up to June 1944.

He was 'dealt with' by the Maquis after the liberation of France.

HMS Fidelity

The ship was originally called the Le

Rhin and was a British made, but French owned tramp steamer, used

in the Mediterranean, displacing 2456 tons.

It was only after her hand over to the Royal Navy that she was armed and

used as a 'Q-Ship', although in WWII they were termed as 'Special

Service Vessels'.

Langlais's real name was Claude Andre Michel Peri. He was born in French

Indochina.

As for the WRNS officer, her real name Madeleine Bayard, also known as

Madeleine Barclay. Peri had 'teamed up' with her in French Indochina and

had operated for the French Secret Service there before the war.

Bayard had travelled back to Europe with Peri and was aboard Le

Rhin when it sailed to England. Part of the deal for the

hand-over of the ship and its cargo, was that along with the rest of the

crew who were to be enrolled in the RN, Bayard would become a WRNS

officer, serving on board Fidelity.

The above information was

received, with thanks, from Paul

Young

who has been researching HMS Fidelity and her crew.