RAF PILOT* TALKS AFTER 20

YEARS OF SILENCE

THE SECRET OF FRÉTEVAL

For 3 months, from May till August 1944, 152 Allied airmen were in German occupied France, directly under the noses of the Germans, hidden in the woods of Fréteval.

It was mainly due to the boldness and discretion of the French resistance fighters, the Resistance, who put their own lives at risk to save their Anglo-Saxon allies, that this secret camp was not discovered by the constant German patrols.

For a long time after the war, the Fréteval affair was kept secret. For the first time last year a few odd rumours started. Our correspondent in London, Gustav Mauthner [a Swiss journalist working for the Austrian newspaper Die Weltwoche: the story was also picked up by Elseviers Weekblad, a Dutch paper], talked to Clifford Hallett, who himself lived in this hidden camp between Chartres and Vendôme, about this heroic war effort that was unknown up to now.

Sgt Cliff Hallett, the Mid Upper Gunner 'taken in Leeds, age 21' |

Hallett's Halifax MZ630 ZA-S of

No.10 Squadron at RAF Melbourne took off at 2233hrs on 2nd

June 1944. It was shot down on 2nd June 1944 by two German

fighters during an attack on the shunting yard in Trappes near

Paris, one of the most important in the whole of France.

The aircraft was set on fire in the mainplanes and both port engines. It was abandoned and crashed at St-Andre-de-l'Eure (Eure), where the two of the seven man crew who were killed - F/O A A Murray (pilot) and W/O J Williams (Wireless Operator) are buried in the town's communal cemetery. Sgt E F Stokes (Bomb Aimer) was so badly injured after his fall that the only thing he could do was wait for the Germans to capture him and he was admitted to hospital with a broken leg. |

Three others got away and were taken to a brothel in Paris by the Resistance. Unfortunately, the Germans discovered them and took them to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. They all survived - Sgt J N Osselton (Flight Engineer), F/O S A Booker (Navigator) and Sgt T Gould (Rear Gunner).

Hallett landed with his parachute on the airfield at St Andre. He heard voices but not being sure whether they were French or German, he ran away. In the pouring rain he crawled on all fours through a wheat field, scraping the skin of his legs. When he felt safe, he rested in the darkness.

| At daybreak, he was woken by unseen

men talking in German and saw a sign nearby written in German

Eintritt Verboten (Keep Out). He had slept on the

edge of an enemy camp - still in his RAF uniform.

Finally, a farmer took him in, gave him coffee and bread and a bed. In the afternoon a stocky giant of a man came to him. The farmer called him Michel. He was head of the Resistance in that area (Hallett subsequently heard that he had been captured a week later and shot). Michel interrogated him first, then had the air force blue uniform burnt and gave him a new set of clothes. He was then taken to a family in Nonancourt where he stayed for 2 [actually 3]weeks. Then he and three other RAF airmen were taken south in an old Fiat by the Resistance. Even their French companions could not tell the Englishmen what was going to happen to them. |

'Hiding place at Thorossov's for first three weeks prior to move direct to Freteval' |

They were taken to meet a tall man, who looked like a civilian and who introduced himself as Lucien Belgrade, on the edge of a wood. He explained to them that in these woods was a camp for men in the same situation as them. Like Michel, he first interrogated them to be sure they were not German spies. Berlin had ordered some of their men to slip into the Allied escape organisations. One of these spies, a Belgian, had handed hundreds of airmen over to the Gestapo. "If you are not what you seem to be, you won't live long." warned Lucien.

This man, a Belgian colonel called Lucien Boussa, was not only head of the camp; for the inhabitants of this oasis, who saw little of the Resistance, he was also the heart of the whole organisation. He was one of the founders of Fréteval. From his headquarters (to start with a game keeper's house, later a busy railway station), he had radio contact with London every night. He frequented the local public houses mixing jovially with the Germans, who had a munitions camp and tank site there.

As opposed to conventional army ways, he ordered the Resistance not to hand out guns to his proteges. He reckoned that if they were discovered, they would take the quick way out and he wanted to avoid unnecessary bloodshed. To the young RAF airmen he was like one of them, a 20 year old; in actual fact he was born at the beginning of the century.

Up to the beginning of 1944, M.I.9 had had all stranded men, who were more valuable than planes for winning the war, brought to the Spanish border by train with the help of the French resistance and then evacuated either via Gibraltar or Lisbon. However, as from March 1944 the French railway system had been almost totally destroyed by Allied bombers in preparation for the Normandy invasion so the Comet Line could no longer be used. The organiser, the Belgian Baron Jean de Blommaert, called The Fox by the Germans, was called to London for talks with M.I.9. The result was that Colonel Boussa, up to then, commanding officer of a Belgian squadron of the RAF, was ordered to France with the apparently senseless job of setting up a collection camp between Vendôme and Chartres for the stranded airmen until they could be freed by the imminent invasion.

With Fréteval, an historic area was chosen, going back to the times of the stormy relations between France and England. In 1170 the English King Henry II had his last reconciliation there with Thomas a Becket, Saint Thomas, who was murdered a few months later in Canterbury. Towards the end of the same century, Richard the Lionheart conquered King Philipp August of France, who had broken their contract, after his escape from prison.

That the Resistance was actually prepared to try and realise these plans proves their courage. The Germans had Touraine very much under control like everywhere else. A few months earlier in February 1944, ten patriots, who had harboured the crew of a shot-down Allied plane, had been deported to a concentration camp (only four of them survived the ordeal) and at the end of March 1944 31 local members of the Resistance had lost their lives.

In spite of everything, all helped. A gendarme from the town of Cloyes, Omer Jubault, who had already organised attacks on the Germans, worked out plans for a camp in the extensive woods that he knew so well, showed them to Boussa and was given permission to go ahead.

| A baker and a station master, a miller,

forester, farmers and farm workers, men, women and children,

dozens or maybe even hundreds of people were roped in. Tents

were brought, cattle, meat, bread, milk, vegetables and eggs

were delivered regularly from a radius of 30 km inspite of

strict rationing.

One thing could not be obtained for the Englishmen: their beloved tea. However, they consoled themselves with the barrels of red and white wine. In the undergrowth of the woods the camp was not easy to see, as long as the Germans did not actually walk right into it. In order to avoid discovery, all occupants had strict orders not to talk louder than a whisper. There were men constantly on guard to warn of the approach of unwanted visitors - German officers sometimes went hunting in the woods of Fréteval. |

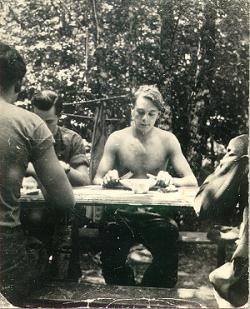

'Feeding time at the Foret - yours truly has back to camera'. The details who is actually in this photo are being checked. |

Every morning after the Reveille at 6 am, all the tents and other equipment were covered with fresh branches so that the camp could not be seen from the air. The airmen made their own furniture, tables and benches, out of tree trunks and branches.

They improvised chess boards complete with pieces and even made wooden golf clubs and balls for their 'Golf Club'. For a while poker was the main game but this came to an end when Hallett won all the money in the camp, at the time around £600, within 2-3 weeks. Up till then he had never played the game before but became a champion within a few days. After this, the other members of the camp asked Boussa for credit but he refused saying wisely that gambling could put an end to the good atmosphere in the camp.

As the days passed, life got boring. Most of the time was spent with whispered conversations. Occasionally they got a glimpse of the pretty farmer's daughter, who came to get water at the well at the edge of the woods, showing off her charms. On Sundays all eyes turned to the meadow where her sister looked after sheep and relieved their boredom a little. However, there was no direct contact with the fairer sex but plenty of talk about it. Once a week was the welcome visit of Albert Barillet who relieved the camp of that growth that wasn't necessary for their safety: M. Barillet was the local barber.

The ill and injured were well looked after. An 80 year old widow Mme. Despres, who had an estate about 10 km away from the camp and who spoke fluent English, turned her house into a sick bay with on average 5 patients. The doctor from Cloyes, Dr. Feyssier, and his son, also a doctor, treated the patients and also visited the camp regularly to see to the men with small ailments. One of these was Hallett. It was not discovered till he got to Fréteval that he had an internal injury as a result of his parachute jump and for a time he had to be carried to the poker games. He explained: "I was put on a special diet and practically treated like a special guest."

Occasionally Fréteval only just escaped discovery**. One morning Virginia d'Albert Lake, an American married to one of the leaders of the Comet Line was stopped by a German patrol asking for information while she was transporting some airmen on the road. She was betrayed by her accent. Her proteges escaped and with great presence of mind she swallowed the sketch showing the position of the camp just in time. (She survived Ravensbruck).

Another time towards the end of July, the farmer Maxime Plateau was taken prisoner by the Germans. He worked on the same farm where Emile Zola had written his novel La Terre. The Germans arrested him in connection with weapons being parachuted down for the Resistance. That had nothing to do with the camp in Fréteval and in spite of torture Maxime Plateau never mentioned it. He knew exactly where it was - he was one of the main suppliers of food there.

During the month of June the camp filled up. Boussa decided to set up a second one about 10 km away in the extensive woods. If the first one was enlarged with more tents, the risk of being discovered would be even greater. This was one of the reasons,but not the main one, for opening a new camp. This paradise had no Eve but a Serpent. In Fréteval everyone was for agreement: same hope of freedom and victory, same fate, same type of weapons, same language but the Englishmen and Americans could not stand each other. The differences had become so great that Boussa decided for the sake of peace to separate them.

The English had had enough of the showing off of their transatlantic cousins. As far as they were concerned everything in America was twice as big, twice as good, twice as nice as in England. They naively stated that in actual fact only they could win the war. They did not want to hear that they had not wanted to know about the events in Europe till Pearl Harbour and Hitler's declaration of war forced them to take up arms.

The English took revenge in their own way. Three times American bombers had tried to destroy a bridge within sight of the camp and had failed each time. Then one night three English Mosquitos appeared and promptly destroyed the bridge. Now the RAF men taunted the Americans, which they could not stand. Whether the Americans for their part had any complaints about the English remains a mystery.

However, the RAF helped to prevent further unpleasantness. They sent down tents for the new camp by parachute. This was one of the few occasions when they directly helped. Only on three or four occasions had things fallen from the sky from them - cigarettes (Gauloises of course, as if any Players or Gold Flake had been carried to the Germans by the wind they would have become suspicious) food and - best of all - flea powder. They all got terribly itchy in the woods.

The differences between the English and Americans flared up again later on after the camp had been disbanded. Following directions from London, Boussa had ordered that no-one was to try and reach the invading troops on their own. This would only cause confusion or worse. During August when the Germans were retreating and the troops of General Patton from Le Mans suddenly moved north, Fréteval was in no-man's-land. A plan was made to remove the occupants by Dakota planes but it was then rejected as being too risky. Finally, the Americans were collected by their own tanks and the English and their colleagues from the Commonwealth shortly after by gas-driven buses from the Belgian forces.

In Le Mans, where they all met up again, Hallett wanted to get aboard one of the buses being used for the evacuation but was kicked off the runningboard and "We don't want any damn Limeys here" was shouted after him. He found a seat in the next coach.

As from October he was back in the air, this time with the Air Sea Rescue branch of the RAF. Today, grey-haired and thickened up, he works as manager in the Gas Board in the southwest English provincial town of Taunton.

Other occupants of the camp were not so lucky: one quarter of them fell during the last 8 months of the war in the air over Germany.

When Hallett was invited to fly to Fréteval for the unveiling of the Fréteval monument by the French Minister for Veterans, Duvillard, he was looking forward to meeting old friends, especially Colonel Boussa, again. He had heard that the Belgian, now retired, had come to Cloyes as honorary member of the monument committee to help organise the celebrations.

However, he could only pay his respects to him at the cemetery. Boussa had died in March. A few weeks ago his mortal remains were moved from the place he loved - "France is my second homeland and its capital is Cloyes" - to his first homeland. They are now on the military cenotaph at the magnificent cemetery of Robermont in Lüttich, high above the Maas.

sources

Cliff Hallett

RAF Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War, 1944: W R

Chorley (Midland Counties)

* This was the journalist's headline. Cliff writes: "I originally trained as a pilot in Rhodesia, but was slung off eventually, and I wangled my way back to this country [the UK], to try to put my case to be given another chance at pilot, if not navigator, which was an option given to me in South Africa. The hardened panel of Wing Cos said I was trying to f*** them around, not surprising as they usually dealt with the LMF boys, this being Eastchurch. Their final word was 'you have 24 hours to decide - Air Gunner or the Army' I replied that I didn't want 24 seconds - Air Gunner. They said they had a good mind to bung me in the Army, who were waiting outside for the LMF boys. A very near miss."

** 16 Jan 2012: Cliff adds: I know that Worrall says that only 30 Germans were there but, he didn't arrive in the Forest until several weeks after this event. The facts are that Lucien Boussa came to the camp when he heard what was happening and said that we would not be eating that night.

Further, when he came to our tent it was also to inform me, who could not walk at that time, that should the Germans happen upon us it would be every man for himself and he was sorry but they would have to leave me as they couldn't possibly carry me. Would I try to stall them for 24 hours and then I could tell them whatever I thought I knew.

He then said that he did not know how many Germans were involved. As I knew of the tracking expertise of Everett Adams (the South African Bantu) I suggested he go out and find out the true situation. Boussa agreed to this and waited whilst [Adams] set off. On his return he definitely told us he would guess there were 300 Germans there. Then in the morning he went back again and was able to inform Boussa they had all moved off and we were able to have something to eat.

No other person in the camp had the slightest idea how many Germans there were, only Adams and he did say 300.

Cliff Hallett died on 15th July 2013

last updated 10 Aug 2013