|

" This was a scheme to concentrate evaders in

areas likely to be out of the way both of the Germans and of

the eventual Allied advance, in woodland camps: there was to

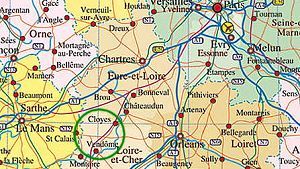

be one near Rennes in eastern Britanny; one near Châteaudun

west of Orleans, and one in the Ardennes, astride the

Franco-Belgian border.

Everyone concerned in M.I.9 and MIS-X was sure that by setting up these camps they would improve the evaders' chances of safety. Still more important, they would lessen the risk to the families of helpers who would otherwise have to shelter them, probably in large and police filled cities such as Brussels and Paris." continued |

|

"In the early part of 1944", wrote Airey Neave ('Saturday'), "I decided that the maintenance of large numbers of men in rural areas, perhaps camping in forests, would need the strictest discipline.

The Surété therefore found for me a Belgian in the R.A.F., Squadron-Leader Lucien Boussa ('Belgrave'). This was a group of the highest quality."

"Room 900 were now able to recruit agents and radio operators who, by their character and training, had the best qualifications for this work. It was a tribute to the successes of O'Leary, Dédée and earlier leaders that I was able to command such support. It was also the reason for the successful outcome of most of 'Operation MARATHON'."

This was a scheme to concentrate evaders in areas likely to be out of the way both of the Germans and of the eventual Allied advance, in woodland camps: there was to be one near Rennes in eastern Britanny; one near Châteaudun west of Orleans, and one in the Ardennes, astride the Franco-Belgian border. Everyone concerned in M.I.9 and MIS-X was sure that by setting up these camps they would improve the evaders' chances of safety. Still more important, they would lessen the risk to the families of helpers who would otherwise have to shelter them, probably in large and police filled cities such as Brussels and Paris.

It was foreseen that retreating Germans might have ragged nerves; Oradour-sur-Glane provided tragic evidence that this foresight was correct. Crockatt was haunted by the spectre of a general massacre of Allied troops or airmen caught at large in occupied territory, and resolved to prevent one if he could.

Neave: "Many of our conferences with the Belgians took place at 22, Pelham Crescent where d'Oultremont and de Blommaert lived in London. In these civilised surroundings, we planned one of Room 900's best schemes. De Blommaert had, since 1942, been one of the leaders of the young Belgian group at 22, Pelham Crescent. He had been recruited from the Belgian Army and proved to be an exceptional organiser. He was tall, blond, and thoughtful. His reticence and thoroughness commanded respect especially with the French Resistance. In August I944 he made a magnificent success of a plan for hiding airmen in the forests near Châteaudun, code named 'Sherwood'."

"Over all of us hung the fear that if the Germans knew that they were losing the war, they would turn to brutal methods and spare no one, even in uniform. The hundreds of Allied aircrew who remained in Belgium and France would still be needed for the war effort. It may have been for this reason that we had greater support from the Air Ministry than before. 'MARATHON' would involve more sorties by the R.A.F. for parachuting agents and supplies than Room 900 had ever planned in the past."

"I did not know how long we should have to wait for the actual landing. I had to assume that it would come some time in the late spring. It was also impossible to tell when our forces would reach the areas of France and Belgium which we had selected for the camps. Even if the lines to Spain and the Shelburne sea evacuations continued until April or May 1944, the number of R.A.F. and American aircrew shot down would inevitably mean that several hundred would still be at large after D-Day."

Several Belgian agents of high quality, notably Baron Jean de Blommaert ('Rutland'), had been sent forward by parachute as far back as the Autumn of 1943 to ensure MARATHON's success. They had the usual difficulties with the Germans. Conrad Lafleur, another Dieppe escaper and one of their wireless operators, was caught in the act of transmission at Reims, but shot his way out of the ambuscade and was rescued by Comet.

De Blommaert had the traitor Desoubrie on his back for a time; escaped by Comet also, in March 1944; and parachuted back into France in April to set up Sherwood, the camp near Châteaudun. Thirty men were there by D-Day, and over a hundred by the end of July, almost all of them airmen; sustained partly by parachute drops of food and stores, partly by what could be bought locally. In the end 152 were rescued by Neave himself and the American Captain Coletta, under guard of a big S.A.S. patrol, by a bus convoy from Le Mans in mid August.

The 'Sherwood' Plan

Neave wrote: On arrival in London on March 9th, de Blommaert spent two days at 22 Pelham Crescent writing his report. We then began urgent discussions about his future and whether it was safe for him to return to France. There was no doubt that he had been extremely lucky, but I felt that if he were able to establish a camp in the countryside and remain as far as possible from Paris and Pierre Boulain, he had every chance of survival. Taking a map of the region Chartres Châteaudun - Orleans, we selected the extensive and thickly wooded area between Châteaudun and Vendôme known as the Forêt de Fréteval. The forest, near the small town of Cloyes, was dense and intersected by rides. Surrounding it were many open spaces suitable for parachute operations.

Our first proposal had been for a series of 'mobile' camps, as far as the Spanish frontier. The airmen would be carried in lorries by road from camp to camp, organised by local resistance workers. They could also move by bicycle. But this scheme was far too elaborate and dangerous. Large numbers of German troops were now travelling by road, owing to our fierce bombing of the railways.

Our later talks developed the principle of 'static' camps, and they determined the final shape of the plan for the Forêt de Fréteval. I gave it the code-name 'Sherwood' after Robin Hood and Nottingham Forest. It was here that airmen and others hidden in Paris would be concentrated. Those who had not been taken off by the Shelburne organisation from Brittany would be hidden near Rennes. Those in Brussels would, as before, be moved into the Ardennes under Albert Ancia. At my final conference with de Blommaert, I proposed to send Squadron Leader Boussa with a new Belgian radio operator, Toussaint ('Taylor') to assist him once the camp had been made ready.

I was well aware that this plan, though original, involved great risks, especially if a large number of German troops were stationed in the neighbourhood of Cloyes, a small market town, three miles from the forest. In spite of the bombing, de Blommaert would have to organise the transfer of the men from Paris by train to Châteaudun. Then they would have to be escorted along country roads for about ten miles to the forest. There was also the crucial problem of feeding them in a forest without discovery. But Free French services reported there were strong Resistance parties in the area and that local farmers and priests were loyal to the Allies. It seemed a good choice for a hiding-place. My main anxiety was that airmen might be involved in a battle if German troops took cover in the forest. Much depended on where the battle for Paris and the Seine took place.

I could see that de Blommaert was excited by the prospect of this operation and that he believed it to be practicable. Ancia, too, seemed shrewd and dependable and I felt I could count on him to organise his camp in the Belgian Ardennes. Thus far, our calculations depended on a study of the map. De Blommaert's first duty would be to make a reconnaissance of the forest and recruit agents in Cloyes and the surrounding villages. He had also a difficult diplomatic task to undertake in dealing with escape lines still in operation.

As the airmen would have to be transferred from Comet, and probably Shelburne, I realised that much would depend on his ability to persuade their leaders of the logic of the plan. In the event, he and Ancia had great difficulty in doing so, though I sent messages by 'Monday' to Madame de Greef at St. Jean de Luz and Yvon Michiels ('Jean Serment') the chief in Brussels, explaining its purpose. It was inevitable that a certain rivalry should grow up among those who had stuck it out in occupied territory throughout the war, and the new arrivals. The landing in France would completely alter their situation. I told de Blommaert to exercise great tact. He was to hand over a sum of money to Comet, explain to them the plan, then avoid Paris and make for the Forêt de Fréteval.

On April 9th I was with de Blommaert and Ancia at R.A.F. Tempsford before they were parachuted to France. The calm and poise with which de Blommaert set off on this second mission after his narrow escape from treachery a month before, won my deepest admiration. Somehow I felt certain that he would survive and that we should meet again, for after the invasion, I planned to lead the expedition to liberate the party in the Forêt de Fréteval myself.

The two Belgians landed on a field at St. Amboise, near Issoudun at two a.m. on April 10th. De Blommaert's parachute became entangled in an overhead electric cable and he had to abandon it. They lay up in woods until five o'clock and saw a man stop and look at the parachute hanging above him. By eight-thirty that morning they were in contact with friends in the neighbourhood who had worked with de Blommaert on his previous mission. Next day they reached Paris where they were able to hide the two million French francs which I had given them. Most of de Blommaert's previous helpers were safe, and he found his flat untouched. I had sent a B.B.C. message to announce his imminent arrival and it was understood by his contacts.

When they made enquiries about Comet, they found that a number of helpers in Belgium had been arrested. Only in the south, where Madame de Greef still held sway, was the line intact. The convoys of airmen from Brussels to Paris soon began again but the number of trains was severely limited by bombing. The moment had clearly come when the camps should be prepared. But the underground conflict with Gestapo agents still continued. In de Blommaert's absence in England Prosper Desitter, 'the man with the missing finger' and Pierre Boulain had remained at large, pretending to be agents of Comet.

At the beginning of May, Pierre Boulain arrived without warning at a secret rendezvous used by de Blommaert, and known only to his closest friends. Providentially, Michou appeared and made warning signs. Convinced that Pierre Boulain was a danger to his whole organisation, de Blommaert made plans to liquidate him. He invited a Free French group to assist, but the man who they claimed to have tortured into confessing that he was Pierre Boulain did not correspond with the description of the man known to de Blommaert and Michou. Was it possible that the Gestapo were employing another Pierre Boulain?

The second phase of this tortuous and risky affair took place in Paris on May 16th, 1944. Pierre Boulain reappeared and, like several traitors at the end of the war, offered to turn double agent. Ancia, accompanied by a Free French 'executioner', asked him to take 500,000 francs to Comet in Brussels, the money to be handed over next day. Pierre Boulain accepted but he was heavily guarded by Gestapo agents who stood in the background. The Free French now asked for freedom of action to dispose of him through their special 'liquidation group'. On May 22nd, de Blommaert, who had left Paris for the forest after his narrow escape, received a laconic message from Ancia: "Le coup est fait mais ça chauffe."

It was later alleged that Pierre Boulain had been shot in the street from a 'liquidation car' which was then chased by the Gestapo. But the same man was also seen a week afterwards. It was not till the liberation that it became clear that Pierre Boulain was the same man as Jean Masson who later, under his real name, Jacques Desoubrie, was tried and executed at Lille. The identity of the man who was shot in the street is a rnystery.

It was time for Ancia to leave Paris and he left to start work in the Belgian Ardennes, while Michou reluctantly fled to Spain. On arrival in London she pleaded with me to send her back to France, but I firmly refused. Had she been captured, she would have certainly suffered the fate of her father and sister.

De Blommaert had already made visits to the Forêt de Fréteval and lie now took up his headquarters near Cloyes. Before leaving Paris, he made arrangements with Phillippe d'Albert Lake of Comet for a system of guides by train to the camp. His contacts with the Resistance at Cloyes, made in April, were of the greatest value. As we had foreseen, he found that farmers, bakers and other tradesmen were willing to supply food for the airmen on the black market.

He also reached agreement with the Resistance that there would be no sabotage or other subversive activity against the Germans in or near the Forêt de Fréteval. It was his hope that the German Army would eventually be forced to retire towards the Seine leaving the forest in a no-man's-land between Le Mans and Châteaudun. This was exactly the position when I liberated the camp in August 1944 and the airmen had hidden beneath the thick foliage for over three months.

On May 13th, Boussa, with his wireless operator, Toussaint, arrived at the forest having travelled overland from Spain. They brought my orders to proceed with the Forêt de Fréteval and other camps as soon as possible. Information which I received from the War Office suggested that, if the landing succeeded, the Germans might be falling back on the Seine in a few weeks. I knew that, with difficulties of rail transport, it would take a considerable time to bring airmen from Paris where over a hundred were reported in hiding.

Boussa was nearly forty, spare, energetic and amusing. He had already been chosen to maintain discipline and morale. To keep a large number of airmen of different nationalities in a forest for anything up to three months would be a difficult assignment. As he was a serving R.A.F. officer of senior rank who had distinguished himself in air combat (he won the D.F.C. in the Battle of Britain and was promoted Wing Commander for this mission) he would be able to enforce the rules of the camps.

He had a strong personality and a sense of command. Since he spoke English well, he was given instructions in security and interrogation of airmen on their arrival from Paris. Success for the 'Sherwood' plan depended therefore on the personal leadership of de Blommaert and Boussa. Their principal problem would be to keep order in the forest and prevent the men, through impatience or claustrophobia, from making attempts to escape on their own.

On May 16th I receive a message on Toussaint's radio set, apparently from the Châteaudun region, announcing his safe arrival with Boussa. He gave details from de Blommaert of a dropping zone near the Forêt de Fréteval for parachuting supplies of food and arms. The latter were on no account to be given to the airmen, who would certainly have been shot as members of the Resistance.

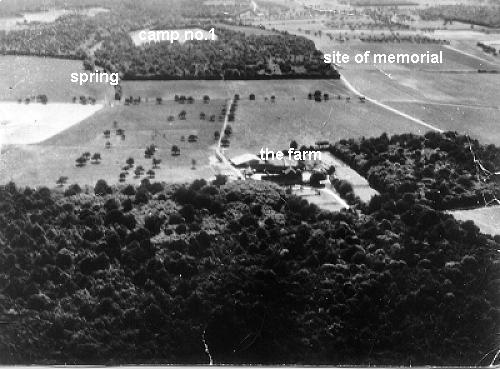

The 'Sherwood' group were lucky in the high quality of the local Free French Forces of the Interior based on Châteaudun. One of the leaders, Omer Jubault, was a gendarme from Cloyes. It was at Cloyes at the Hotel St. Jacques, that Mary Lindell had stayed the night with Windsor-Lewis on their celebrated journey to the demarcation line three years before. Jubault, shrewd and devoted, had already risked arrest for his aid to the Resistance and had now disappeared from the police force. Taking two foresters into his confidence, he selected a site among the trees, well-concealed from the Cloyes-Vendôme road along which German military transport was passing at all hours.

The first airmen were brought by train to Châteaudun on May 20th and taken ten miles across country to Cloyes, in spite of frequent bombing on the journey from Paris. They were hidden in neighbouring villages for the next two weeks. On June 6th, the day of the invasion, thirty Allied airmen were moved into the forest and the camp began.

via Cliff Hallett: not in either book

The 'Sherwood' plan was now in operation, but the difficulties were enormous. For those who did not experience it, it is difficult to imagine life under German occupation at this period of the war. Rationing was extremely strict, and there was virtually no coffee, rice or chocolate, except on the black market. Wine was only available for those doing heavy work. There was practically no fuel or petrol.

Nonetheless, local farmers supplied the camp with fresh meat, vegetables, butter and eggs. Monsieur Viron, a miller, organised the delivery of fresh bread, brought by a young girl in a horse-drawn cart. She made the journey through the forest rides for several weeks, in spite of being machine-gunned by Allied aircraft in mistake for German transport. Two airmen were selected as cooks and worked with charcoal fires which gave little smoke.

The organisation already had a number of tents to shelter the men, but they had been obtained only with the greatest difficulty. One had come all the way from Dunkirk. In the middle of June, I arranged to parachute more at Issoudun, but owing to a misunderstanding, the aircraft returned without dropping its load. For some reason, de Blommaert did not receive the message until too late and there was no reception. A second supply operation (code-named 'Jupiter'), on the night of July 6th/7th, was successful. Fifteen containers were dropped containing tents, food, medicines and clothes.

One of the weaknesses of de Blommaert's position lay in poor radio contacts with Room 900. His own operator, Lemaître, remained in Paris at the service of Comet and seems to have had considerable difficulty with his set, though he did everything possible to maintain contact. He was needed in Paris, where Philippe d'Albert Lake was in charge of the reception and dispatch of evaders to the Forêt de Fréteval, a delicate and essential operation. I also remained in communication with Dumais and Labrosse. After their last sea operation in July from Brittany, airmen held by 'Shelburne' were also sent to the camp.

The second operator, Toussaint, had his set at a village near the forest. He had left a spare set and crystals at Bayonne with the Comet organisation on his journey from Spain. I was not aware of this at the time, and it meant that de Blommaert and Boussa were never quite sure whether their messages were being received by Room 900, and we were often unable to 'raise' Toussaint. Spares were dropped to him on the supply operation 'Jupiter', but there was little improvement in the links with London. It transpired that Comet in Bayonne had sent the spare set for Toussaint by train to Paris. After the camp was liberated, de Blommaert reported that it was either destroyed or stolen when a train was bombed while en route to Châteaudun.

In desperation, Boussa recruited a French operator who claimed to have been trained in England, but had lost touch with his organisers. However, he also failed to make regular contact with Room 900. In spite of this inadequate radio network, the two Belgian organisers set about the establishment of the camp and its administration with remarkable efficiency.

Provided the tents were concealed deep in the forest and away from the rides, the Germans were unlikely to see them. It seems probable that they knew that people were in hiding there, but believing them to be armed Resistance forces, were reluctant to enter.As the camp grew in size, provisions became de Bommaert's most serious headache. After the operation was complete in September 1944, he made a report on the minimum rations required for such an exercise:

per man per day

500 grammes bread

1 litre of milk

2 eggs

400 grammes potatoes

100 grammes meat

8 cigarettes

1 kilo of butter for 12 men each day. If possible, fresh fruit and

vegetables, coffee, tea and sugar."

He managed to obtain most of these

quantities locally, supplemented by food dropped by parachute. Among his

other recommendations were:

"If there is any alcohol, entrust it to a man who will keep it under

guard."

"In the absence of potatoes. dried beans are useful."

"Flour is essential and also sugar, which was very difficult to obtain,

but I managed to obtain some honey."

It seems incredible that by the middle of August, 152 men were being fed in the forest, largely from local supplies. French patriots even risked the curfew to obtain fresh fish for the airmen at night from the River Loir.

De Blommaert has also left some interesting

comments for future guidance on the security of the camp.

It was necessary to have as few people as possible who knew of its

existence, and to have agents to report rumours, and enemy movements.

Sentries should be posted at all times, especially at dawn and

throughout the day, at the entrances to the forest. In the event of an

alarm, he had a plan for speedy escape.

Each man had an 'escape kit' ready prepared with rations and a small

sum of money.

These precautions were similar to those of partisans and 'maquis' in other theatres of war. The main difference between such partisan activity and the 'Sherwood' operation was the presence of over a hundred valuable, unarmed aircrew. It made the task of the organisers exceptionally delicate and they felt the strain of their protection.

At the end of July, the camp numbered over 100 and some were wounded and sick. A male nurse was appointed from among the airmen whose duty was to look after the lightly wounded in an ambulance tent. Severely wounded were hidden by an aged Frenchwoman in her house on the edge of the forest, which served as a hospital. They were treated in secret by a doctor from Cloyes and an American pilot had a successful operation for appendicitis. On the Jupiter supply operation I sent drugs and D.D.T. to disinfect the straw of which the men made beds.

Apart from his immediate entourage, de Blommaert allowed only the doctor and a hairdresser to enter the site. He still found great difficulty in obtaining medicines locally. Had there been better radio contact, I should certainly have been able to send more supplies to him. The sick and wounded suffered in consequence, despite the devotion of their French helpers.

Other administrative problems were stoves, plates and saucepans, some of which were dropped by parachute, others lent by farmers. The tents, dropped on Operation Jupiter on July 6th/7th, were most successful. Prior to this date, many men had been obliged to sleep under cover of parachutes slung over branches or in the large British Bell tent, a relic of Dunkirk and bought at black market price.

When the camp had grown to twenty-five tents, it was decided to create a second on the same model at the edge of the forest at Richeray, six miles away. This was a good site, although there were a number of German ammunition dumps close by. De Blommaert considered that the presence of German guards was an advantage since it kept away the curious and the enemy would never suspect his choice of a hiding-place. Boussa remained in charge of the first camp while de Blommaert took command of the second. When airmen arrived from Paris they were brought to the first camp and interrogated by Boussa. They were then transferred through the forest to Richeray.

Boredom and anxiety were extremely difficult to combat. The men passed their days, thanks to fine weather, sun-bathing and talking. From logs and branches they made themselves tables and chairs. They also created a primitive golf-course but their greatest relaxation was to listen to wireless announcements of the progress of the battle. Important news was posted on a tree which served as a notice board. Senior officers maintained a degree of military discipline. The men rose at six a.m. for breakfast. Then they made up their beds of straw and camouflaged the tents with branches. In this way their morale and health were maintained until their liberation on August 13th, 1944. But their lives were not without dangerous incident.

When bombing and troop movements finally stopped the line to Spain, de Blommaert recruited a number of guides from Comet, among whom was Virginia d'Albert Lake, an attractive American, whose husband Philippe was the chief organiser in Paris. On June 12th, Virginia and her husband attempted to reach the camp with eleven airmen, some on bicycles and some in a farm-cart. On the way from the station at Châteaudun, she was stopped by a German patrol whose officer, speaking in perfect French, recognised her American accent. The remainder escaped, including six airmen in the farm-cart, though they were only fifty yards away from the German troops.

Virginia was taken to the Feldgendarmerie at Châteaudun and interrogated. She explained that she was bicycling towards the Spanish frontier with a friend and this accounted for 127,000 francs and a pencil sketch of the route to the camp which were found on her. The Germans did not appear to have noticed the escape of the rest of the party, who scattered and were later found by de Blommaert hiding in farmhouses. But the Gestapo intervened, and, not believing her, sent Virginia to Ravensbrück concentration camp where she suffered until her release in 1945.

After her arrest, Philippe d'Albert Lake returned to Paris and was able to make contact with another organisation which brought him by Lysander to London. He impressed upon me that de Blommaert was wanted by the Gestapo and known to them as The Fox. Three weeks had now passed since Allied troops had landed on the Normandy beaches. They were now held down by the Germans but sooner or later they would break through and pursue them towards the Seine. I therefore prepared to leave for France, with the rescue of the men in the 'Sherwood' forest as my first objective.

There were more alarms and occasional arrests of guides and other helpers but the camps continued to grow in size without the loss of any airmen. As part of the 'Marathon' programme, smaller camps had been organised in Brittany and northern France. De Blommaert reported that there were fifty hidden in between Chartres and Paris, and sixty between Mantes and Beauvais. Thirty of these were in a camp organised by him at Auneuil near Beauvais. The efficient Paris staff, under d'Albert Lake, had recorded all their names. Lieut. Patrick Hovelacque (Kummel), recruited from the B.C.R.A., who had parachuted to France earlier in the year, reported over fifty in his hands at Chantilly. All these camps were liberated but meanwhile they stood at great risk.

The Race to the Forest

I was determined to carry out their rescue in person and Langley agreed that the AngloAmerican I.S.9 (Western European Area) should train for this operation. It was now essential that I should be in Normandy, and, after handing over Room 900 to Darling, who had been transferred from Gibraltar, I set sail for France. I landed at Arromanches from a motor torpedo boat and established myself not far from Caen. I had a month to wait before the great break-through from the beach-head began and I could start the expedition to the Forêt de Fréteval.

I knew that de Blommaert and Boussa and more than 150 men were waiting impatiently. Lefort, Thornton and I were back at Avranches on August 8th, but our road to the camp was blocked by an enemy counter-attack at Mortain. We therefore summoned all available sections of I.S.9 (W.E.A.) and by-passing Mortain followed Patton's thrust along the road to Laval and Le Mans.

It seemed that my calculations were justified and that Patton's troops were moving rapidly towards the Forêt de Fréteval. From Le Mans the camp was forty-seven miles in the direction of Châteaudun. I arrived in Le Mans on August 10th confidently assuming that American Third Army would attack towards Chartres and Vendôme. I was disconcerted to hear from the staff of an armoured division that they intended to attack north of Alençon and close the Falaise Gap a manoeuvre which destroyed much of the German army west of the Seine.

It was a serious position for me. I had counted on tanks and armoured cars to help me recover the airmen. I did not possess sufficient fire power to deal with any large body of Germans. I had only half a dozen jeeps and a few automatic weapons to effect the rescue of at least 150 people in enemy-held territory. Nor was there any clear information about a German withdrawal from the Fréteval area. German battle-groups were reported between Le Mans and Châteaudun, and I had no direct communication with the camp.

After a rapturous reception in the main square of Le Mans, I made my headquarters at the Hotel Moderne which the Germans had just left, to find an excited mass of war correspondents and Free French with rifles. The only thing to drink was cheap white wine which did not seem to prevent an atmosphere of rejoicing. But I was worried and alarmed. I sat in the dining-room with Thornton and Lefort with a map of the region, planning the route to the forest. I was going to be responsible for a terrible tragedy if things went wrong, and I began to search around for means of obtaining transport and armed protection.

In the afternoon, Thornton and I drove to the headquarters of American XV Corps, north of Le Mans, and begged a worried Staff Officer for a few trucks and armoured cars. I explained that half the men in the camp were from the American Air Force and I feared a tragedy if they waited any longer. I believed that, hearing the sounds of battle, some of them would break away and join Resistance forces in civilian clothes. We had heard grim stories of massacre by the S.S. and seen evidence of it on our way. In some cases whole families had been shot and their houses burned. The Germans were in a mood of panic. They were harassed in their retreat by the French underground who mined the roads, threw petrol bombs at tanks and sniped at them all the way to the Seine and beyond.

These arguments failed to convince the American Staff and their Corps Commander. They had their orders to wait for a move on Alençon and they could spare neither troops nor transport. They declared the rescue operation to be impossible without light tanks. We returned to Le Mans greatly depressed, but in the courtyard of the hotel found a large number of armed jeeps. Standing by them were troops in maroon berets. This was a remarkable piece of luck for me and even more for the inmates of the Forêt de Fréteval. They were an S.A.S. squadron under the command of Captain Anthony Greville-Bell and consisted of four officers and thirty-four men. They had completed their mission in Brittany but, finding little to do there after the German withdrawal on Brest, had decided to move east and await orders at Le Mans.

In high spirits, I hurried into the hotel and found Greville-Bell in the lounge. He was a dashing young officer with a D.S.O., ideally suited to 'private warfare'. and no respecter of red tape. I could not have found a more suitable person to help me in this adventure. His troops would be a great advantage if we met opposition on the way to the forest and most important of all, he had his own radio communications with London. To add to these welcome friends, a group of twenty-three Belgian S.A.S. arrived that evening from south of Le Mans.

Greville-Bell sent a signal to S.A.S. headquarters in London asking for permission to take part in the operation, which he received the following day. S.A.S. headquarters also provided indirect communication with Darling at Room 900, which was without news of me. For several days messages from London had arrived in Normandy, demanding the whereabouts of 'Saturday'. Without the aid of S.A.S., the operation would have been impossible.

On the following morning, August 11th, I was studying the map at the Hotel Moderne. Like all those days of liberation, it was fine and hot. The war correspondents had left to report the battle of the 'Falaise Gap', and the S.A.S. were cleaning their weapons and checking ammunition in the courtyard. There was still no transport for the airmen. I sent Thornton and Lefort into Le Mans to French Resistance headquarters in the hope that we could requisition local buses. It seemed an unmilitary request, but the Resistance were delighted to help. They scoured the town and found a few large coaches painted grey which had been left behind by the Germans. We were again lucky, for in their hasty retreat the Germans usually commandeered all they could find, including horse-drawn vehicles.

The buses were fitted with the familiar charcoal burners to supplement the absence of petrol and needed considerable maintenance. The possibility of a breakdown between Le Mans and the forest was not pleasant, but there was no alternative. Later in the morning, Thornton and Lefort returned with local Resistance leaders and we sat down to a discussion of the rescue plan in the hotel dining-room. We were interrupted by a commotion in the lobby and the appearance in the dining-room of Boussa and M. Viron, the miller who had been supplying bread for the men. Running the gauntlet of German patrols and trigger-happy partisans, they had driven from Fréteval. I was delighted that Boussa was safe, but somewhat anxious at this exploit.

"You must come and fetch the men immediately, mon Commandant," said Boussa. He was strained and excited, and I felt much sympathy for him.

"There are no Germans at the forest. They have pulled out towards Chartres. It is quite safe for you to come. If you do not, the men will start escaping on their own. Already some of them have gone, and are in surrounding villages. Many of the local people are already showing the French flag. It will be dangerous if the Germans come back and take reprisals."

The dangers of the situation were obvious to me, but the French leaders explained that the transport was not yet ready. They had evidently been over-optimistic.

"Where are these vehicles?"

Volubly, they gave a number of garages in the town and the names of the proprietors. They had not yet found the drivers, though, in the state of confusion which reigned in Le Mans, this was understandable.

"How long do you need to get everything ready?" I asked: "At least twenty-four hours, mon Commandant."

I turned to Boussa. I fully shared his impatience. "Our main difficulty is that we have not been able to obtain American transport and troops as they are advancing towards the north. I think you must go back to the camp and tell the men that they will have to wait at least forty-eight hours. There might be a disaster if we appear without sufficient transport, and you must give direct orders that they are on no account to leave the camp."

Boussa looked crestfallen. "The men are very excited and Jean de Blommaert and I are finding it very difficult to keep them calm."

I was embarrassed at having to show such caution. Captain Peter Baker, a young officer of I.S.9 (W.E.A.), volunteered excitedly to go to the camp. I knew that he had visions of changing into civilian clothes and making his way to Paris to write an article for an American newspaper. It was no time for heroics and there would be serious trouble if these unarmed pilots were captured or wounded.

We talked for some time about his proposal. I was anxious not to restrain such dash and enthusiasm. The French were declaring that they 'controlled' the road to the forest, but it seemed that, if Baker could get through, he might be able to explain the situation to the men. I let him go with five S.A.S. troops under an officer. They were fired on by a small group of Germans and one man was slightly wounded but they reached the camp that afternoon and helped to sustain morale. Boussa and the courageous M. Viron in his baker's van returned at the same time.

I said to Boussa in the courtyard of the hotel that we would try to get to the forest on August 14th. We had already decided on a rendezvous with the party at a point on the edge of the forest on the road between Vendôme and Cloyes. There remained considerable difficulties. Only half the buses had drivers. Nearly all the young men of the town had joined the Resistance and were far away or had been deported for work in Germany, and the vehicles still needed mechanical attention.

Next morning further efforts were made to obtain American military transport, which remained standing outside Le Mans waiting for orders. It was maddening to see rows of lorries and trucks parked at a Divisional headquarters, but the American commanders were suspicious of the exotic crowd of armed patriots who accompanied me. They were not prepared to risk their vehicles on so long a journey into country which had not been cleared of the enemy without the use of tanks. There was nothing to be done except return to the hotel. The airmen would have to wait another day.

At noon, as I was preparing to send another officer to the forest, de Blommaert appeared, smiling, but impatient. He had come from the forest with Monsieur Viron. My delight at seeing him safe was sadly affected by what he had to say.

"The men are terribly disappointed that you have not come. I assure you that it is safe. This morning several of them have broken away from the camp and are celebrating with the inhabitants of the village of St. Jean-Froidmentel. All the flags are out and people are bringing their best wines out of the cellars."

I could picture what was happening, and my anger mounted against the Americans. It was obvious that with S.A.S., I could have moved to the forest and remained there overnight. Without the transport, however, we could not have brought the men to safety. Our presence in the forest would certainly have alerted the Germans. The prudent course was to make a dash there when the buses were ready and get the men back before anything happened.

The Americans continued to report German rear guards in the neighbourhood. A fight between these rear guards and the S.A.S. would obviously put the airmen in extreme danger. They would probably scatter and be difficult to collect. I was now determined to do the operation in one piece, though the reproachful looks of de Blommaert were hard to bear. He insisted on returning to the camp for the night.

We sat down to a lunch of American rations and white wine, gloomily uncertain about the buses. In the afternoon, I received a message to go to one of the main squares in Le Mans. There, decked with flowers and French flags and guarded by civilians with rifles, was a collection of sixteen coaches and trucks. I was assured that they were all in working order and though the operation seemed comic, I decided that we could wait no longer. The whole party would leave the following morning.

My varied collection of 'troops', some in uniform, some with Free French armbands, assembled at eight a.m. on August 14th outside the hotel. They numbered about 100. it was a fine, hot morning and in high spirits we set off along the road to Vendôme with a patrol of S.A.S. ahead of us. I had given orders to travel as fast as possible. Within three-quarters of an hour, despite much spluttering from the 'buses' we turned off through gay villages towards Cloyes and up the road through the forest to the rendezvous. It was easily found. At a clearing beside the road, we found de Blommaert and Boussa with a large crowd, cheering and waving. It was far more like the departure for a seaside outing than the end of the extraordinary 'Sherwood' plan.

The airmen were lean, bronzed and dressed in rough French working clothes. Some were angry and impatient. A few had disappeared and ten were taken off by two American tanks on the edge of the forest. I shook hands with Omer Jubault, the gendarme who had done so much to make the plan a success. I could only apologise for our failure to arrive before. Then we turned round and set off at a hot pace back to Le Mans.

The S.A.S. searched the villages en route and picked up a few tattered and demoralised German prisoners whom they pushed into the coaches beside the airmen. It was hard to believe that this was the end of operation 'Sherwood'. In my jeep were de Blommaert and Boussa and I could see that they could hardly realise that their extraordinary feat had been accomplished, after three months of suspense. It was fortunate that we had not delayed the expedition longer. That evening German patrols were reported in the forest, alerted, apparently, by the activities and rejoicing on the road to Cloyes.

Just before noon, we were back in Le Mans where a meal had been organised with American rations at a former French Army barracks. The Americans seemed to have realised the significance of the arrival of a large number of their airmen, who loudly demanded transport back to base. Army trucks and lorries at last appeared outside the barracks and after lunch the whole party left along the road to Laval where, sad to relate, some of them were injured by the overturning of one of the vehicles.

In a signal to Donald Darling on the S.A.S. radio set, I stated that the total number of men collected was 132. They were Americans, Canadians, New Zealanders, Polish and British. De Blommaert stated that the total roll call of the camp the day before had been 152, and it was assumed that those missing had either been collected by American tanks or were hiding in villages. Nearly all went back on flying operations and thirty-eight of them were killed in action before the end of the war.

To have planned and executed a scheme to hide and feed 152 airmen under the noses of the German Army and the Gestapo was an outstanding achievement. In a personal signal to Crockatt at M.I.9 that afternoon, I recommended de Blommaert for the D.S.O., since he had begun the camp and had already done great service for the Comet line, and Boussa for the M.C. They both received immediate awards as well as the French and Belgian Croix de Guerre. Omer Jubault and members of the Paris organisation of Sherwood and Shelburne were also decorated.

Dedication of the memorial 11 June 1967 (via Hallett)

For many years Operation 'Sherwood', except to those who had taken part, remained an unknown story of the French Resistance movement. In 1966 a committee was formed under Omer Jubault, now retired from the French police, to erect a memorial at the place where my 'army' had collected the airmen over twenty years before. Funds were raised to which the Royal Air Force Escaping Society and many other organisations contributed. On June 11th, 1967, at an official ceremony, Jean de Blommaert and I laid wreaths on the grave of Lucien Boussa at Cloyes. He had died suddenly at the Hotel St. Jacques in March.

The same afternoon, in the presence of a crowd of five thousand and full military honours, Monsieur Duvillard, the Ministre pour Ancien Combatants, unveiled a plain stone column at the edge of the forest with the inscription: